Quick Look

- The Fed raised interest rates by 50 basis points this week.

- Economists expect a smaller 25-basis-point hike on Feb. 1, 2023.

- Interest rates on credit cards and mortgages will continue to increase as a result.

- Savings account yields could increase as well.

- The Fed hopes to stop hiking rates in Q1 or Q2 2023, but that depends on inflation and the economy.

The Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve hiked the closely watched federal funds rate by 50 basis points at its meeting this week. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell announced the move at 2pm Eastern Time on Wednesday, Dec. 14.

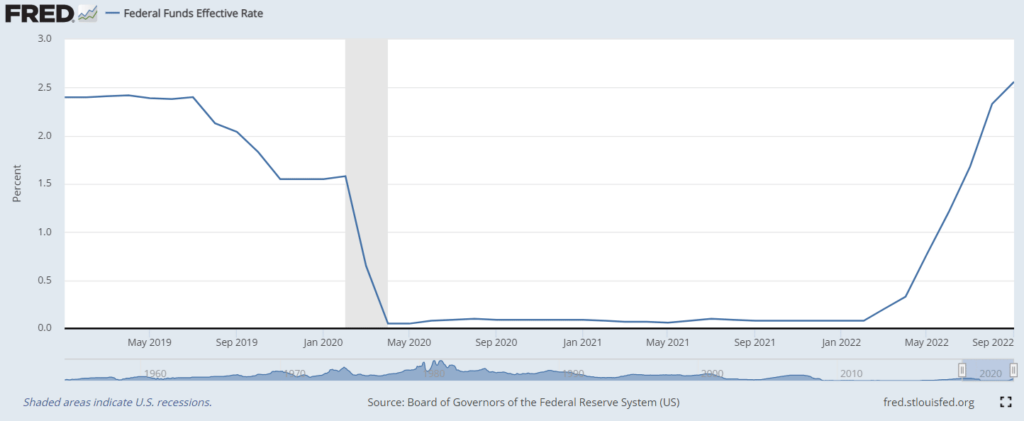

The FOMC’s December rate increase is the latest in a series of hikes beginning early this year. It will boost the target federal funds rate to a range of 4.25% to 4.50%, a 50-basis-point jump from the November range and a 425-basis-point increase from the beginning of 2022. The higher rate immediately increased borrowing costs for consumers and businesses.

Find out what to expect from the Fed’s next meeting, what it means for the broader economy, and how you can prepare your finances for what’s to come.

The FOMC’s December 2022 Meeting

The market’s expectation for a 50-point hike came amid commentary by key Federal Reserve governors, including Christopher Waller and Chair Powell himself, that the FOMC could moderate its aggressive stance.

Motley Fool Stock Advisor recommendations have an average return of 397%. For $79 (or just $1.52 per week), join more than 1 million members and don’t miss their upcoming stock picks. 30 day money-back guarantee. Sign Up Now

The Fed raised rates at an unprecedented pace in 2022 amid persistently high inflation, and recent economic data suggest their efforts have paid off. The labor market is moderating, the red-hot housing market is cooling, and most importantly, inflation appears to be peaking.

Unlike in November, when virtually everyone expected a 75-point increase, there was some uncertainty around the size of the December hike. The Fed could have (but didn’t) surprise the market with another 75-point hike. Less likely but still possible was a 25-point raise. In actuality, the consensus view of a 50-point hike panned out.

The market would have taken a 75-point increase as a sign that the Fed believes inflation isn’t yet under control. Stocks and bonds would likely have sold off hard in this scenario.

A 25-point increase would have sent the opposite signal about inflation, but could also raise concerns that the Fed thinks the economy is in worse shape than it appears. It’s not clear how the market would have reacted to a smaller-than-expected hike.

As is customary, traders held their positions until Chair Powell’s customary post-announcement press conference, when he answered questions from financial journalists desperate for insight into the FOMC’s thinking. If past is prologue, his answers could precipitate a new round of market volatility. (Or not.)

We weren’t in attendance, but we’d ask him these four questions if we could.

Why Is the FOMC Raising Interest Rates Again?

In a word, inflation.

Despite signs of a peak, annualized inflation remains above 8%, far higher than the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. The FOMC appears to be rerunning the Fed’s playbook from the early 1980s, when then-Chair Paul Volcker pushed the fed funds rate to 19% in a bid to quash sky-high inflation.

How Do Fed Funds Rate Hikes Affect the Economy?

The federal funds rate is a key benchmark interest rate for banks and other lenders. Raising it increases the cost of the short-term loans most financial institutions need to operate normally. They pass those costs to their borrowers via higher interest rates on credit cards, real estate loans, and business loans and credit lines.

The correlation isn’t always perfect, but economic activity tends to slow as borrowing costs increase. Consumers buy less on credit and put off major purchases. Businesses delay or cancel planned investments. They may lay off contractors and employees if they can’t control costs elsewhere.

With businesses making less money and fewer people drawing paychecks, a feedback loop develops. Demand for goods and services falls. The economy slows further, maybe tipping into recession. Declining demand helps cool inflation, but at the (hopefully temporary) cost of livelihoods and profits.

When Will the Fed Stop Raising Rates?

Economists expect the federal funds rate to top out in the first or second quarter of 2023. They expect a terminal rate — the highest the Fed will let the funds rate get before it takes action — of between 4.75% and 5.25%, according to the FedWatch predictive tool. But some banks expect a terminal rate closer to 6%, which would cause even more economic pain.

Once it hits the terminal rate, the Fed will probably keep rates steady for a while, unless the economy is in really rough shape. Then it’ll pivot — market-speak for beginning a rate-reduction cycle. Markets love it when the Fed pivots because it means lower borrowing costs and, usually, higher business profits.

Will the Fed Cause a Recession?

According to Reuters’ October 2022 economist survey, it’s likelier than not. About 65% of respondents predicted a U.S. recession by the fourth quarter of 2023.

Chair Powell seems unbothered by the possibility of a recession. Though he hasn’t said outright that he’s rooting for a recession, he’s on the record saying that asset prices (especially real estate values) need to come down. And in August, he told attendees at the closely watched Jackson Hole Economic Symposium that the Fed’s commitment to fighting inflation was “unconditional.”

The stock market tanked as he spoke.

What the December Rate Hike Means for Your Finances

What does the Federal Reserve’s latest interest rate hike mean for your wallet? Four things:

- Your Credit Card Interest Rate Will Go Up. Like clockwork, credit card companies raise interest rates in lockstep with the Fed. Expect your credit card rates to increase by 50 basis points within a week of the rate hike.

- Your Savings Account Yield Could Increase. The relationship between savings yields and the federal funds rate isn’t quite as strong, but it’s still there. Banks just tend to raise yields more slowly than the Federal Reserve because they make money off the spread between what they pay customers and what they themselves pay to borrow.

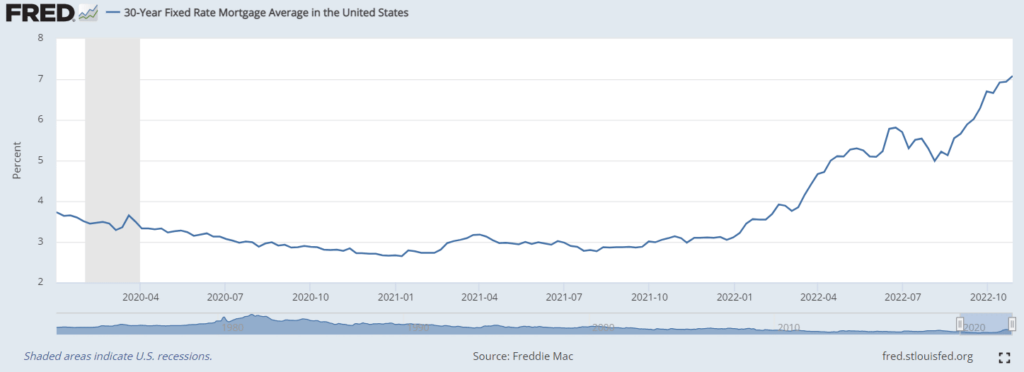

- Your Fixed Mortgage Rate Won’t Increase. Your fixed mortgage rate is, well, fixed. At this point, refinancing probably isn’t in your best interest, so just sit back and enjoy the rate you locked in when money was cheaper. If you have an adjustable-rate mortgage, your rates will go up, and it might be time to consider refinancing before it gets worse.

- Your Retirement Portfolio Will Remain Volatile. It has been a rough year for stocks and bonds. We’re not in the business of stock-picking, but it’s a fair bet that market volatility will persist due to ongoing economic uncertainty and uncertainty around just how far the Fed will go to fight inflation.

Your Personal Finance Playbook: What to Do As Interest Rates Rise

The negatives of higher interest rates outweigh the positives, but it’s not all bad. Do these things now to protect yourself and make your money work harder.

- Move to a High-Yield Savings Account. After the Dec. 14 hike, the most generous savings accounts will yield 3.50% or better. That’s much lower than the inflation rate, but it’s better than traditional big banks’ paltry savings yields, which haven’t budged during this hiking cycle. Move your money if you haven’t already.

- Pay Off Your Credit Card Balances. You should never carry a credit card balance if you can avoid it, but it’s especially painful when interest rates are high. Make a plan to pay off your existing balances as soon as you can. If you need help, work with a nonprofit credit counseling agency.

- Buy Series I Bonds Before May 2023. They’re your best bet to fight inflation, better than any savings account. Rates reset twice per year, on Nov. 1 and May 1. With inflation probably at its peak, the May 1 rate is likely to be lower than the current 6.89% rate, which is already down from 9.62% earlier this year.

- Buy a New Car Sooner Than Later. Auto loans are a weird bright spot for consumers so far this hiking cycle. Dealer financing rates haven’t increased much since 2021 as car dealers fight softening demand for new cars while undercutting banks and credit unions that also offer auto loans. Plus, both new and used car prices are coming down to earth as supply increases and demand cools.

How We Got Here: Fed Funds Rate Hikes in 2022

The FOMC has raised rates at a breakneck pace in 2022.

The current target rate of 3.75% to 4% is 375 basis points higher than it was at the beginning of the year. The gap is likely to increase to 425 basis points after the December meeting.

Markets and economists expect a 25-point rate hike at the FOMC’s next meeting, which concludes on Feb. 1, 2023, and another 25-point hike at the FOMC’s March 2023 meeting. After that, expectations are much less clear. Some believe the Fed will pause hikes indefinitely, while others expect cumulative increases of as much as 100 basis points more in 2023.

It all comes back to what the economy does in the meantime. Hotter-than-expected inflation readings or job growth numbers in Q1 2023 could convince the Fed to hike longer and higher than expected, even if it results in a longer, deeper recession than forecast. If the economy looks to be cooling faster than anticipated, it’s not out of the question that the Fed does nothing on Feb. 1.

In that case, markets will inevitably look ahead to the next big question of the current Fed cycle: when and by how much it’ll start cutting the federal funds rate.

| Meeting Date | Fed Funds Rate Change (bps) |

| March 17, 2022 | +25 |

| May 5, 2022 | +50 |

| June 16, 2022 | +75 |

| July 27, 2022 | +75 |

| Sept. 21, 2022 | +75 |

| Nov. 2, 2022 | +75 |

| Dec. 14, 2022 | +50 |

| Feb. 1, 2023 | +25* |

The rapid increase comes after two years of rock-bottom interest rates. The Fed slashed rates by 150 basis points between February and April 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic pummeled the economy. They stayed near zero through 2021.

One More Fed Move to Watch: Quantitative Tightening

The FOMC’s interest rate decisions might grab headlines, but they’re not the only moves the Fed makes to steer the economy.

Since the Great Financial Crisis of the late 2000s, the Fed has been in the business of buying, holding, and (occasionally) selling U.S. government bonds and other government securities. When the Fed buys securities, it’s called quantitative easing (QE). When it sells them or allows them to mature without replacing them, it’s called quantitative tightening (QT).

Quantitative easing increases the U.S. dollar supply, which is why some say the Fed “prints money” in response to economic weakness. Quantitative tightening decreases the dollar supply, though you don’t hear much about the Fed “burning money” to fight inflation.

Quantitative Tightening in 2022

The Fed bought more than $4 trillion in government securities between early 2020 and early 2022, adding to a sizable stockpile left over from the Great Financial Crisis. It began QT in June 2022 and accelerated the pace in September.

Since then, the Fed has reduced its balance sheet by about $95 billion each month. But with nearly $9 trillion still on its books, it’ll take more than 7 years to fully unwind its purchases. That’s far longer than economists expect the current cycle of interest rate hikes to last — and assumes no economic crises that demand quantitative easing between now and then.

Why Quantitative Tightening Matters for You

QT isn’t some abstract high-finance maneuver. By increasing the supply of U.S. government bonds, it puts upward pressure on rates, compounding the effects of fed funds rate hikes. For example, the yield on the closely watched 10-year U.S. Treasury bill jumped from about 1% in January 2021 to about 4% in late October 2022.

The combined effect of QT and fed funds rate hikes shows up in interest rates tied to both benchmarks, like mortgage rates. That’s why the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage rate increased by about 450 basis points between January 2021 and October 2022 — compared with just 300 basis points for the federal funds rate.

So if you’re in the market for a new house or want to open a home equity line of credit soon, the fed funds rate won’t tell the whole story. If the Fed accelerates QT, bond yields — and thus mortgage rates — could continue to rise even after rate hikes cease and inflation floats down to historical norms.