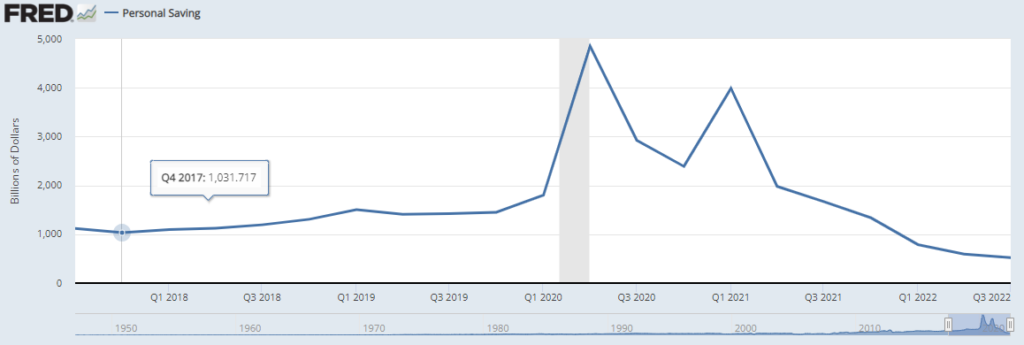

Americans’ personal savings have absolutely cratered since the middle of 2020. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the dollar value of our collective piggy bank declined from nearly $5 trillion in the second quarter of 2020 to just $626 billion in the the third quarter, or $15,990.59 per person. And it’s still dropping.

This is by far the biggest personal savings decline on record. It comes at a time of historically high inflation and a looming recession. It’s not good.

Even if your personal financial position is strong, the personal savings crisis affects you. Millions of people live paycheck to paycheck, with no savings at all, and thousands more join them every pay period. When the economically vulnerable fall on hard times, the economy suffers, affecting people up and down the income and wealth scale. So spend a few minutes with our personal savings analysis to find out how we got here and where we might be going.

What Do You Mean $15,990.59 Lost for Every American?!

No, every American didn’t literally lose $15,990.59. Many didn’t have 16 grand to lose in the first place.

But on average, Americans’ extra cash declined by $15,990.59 per person between March 2021 and October 2022. It’s still falling, but this is the most recent figure we have.

We got these numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ monthly Personal Income and Its Disposition data set. It’s a comprehensive measure of how much Americans earn, spend, and save each month.

To calculate the per-person loss for each month, we divided the bureau’s total personal savings figure by the total U.S. population (approximately 332 million). For March 2021, we got $17,269.61 in personal savings per person. For October 2022, we got just $1,279.03. The difference: a whopping $15,990.59.

This data set isn’t the only personal savings measure the U.S. government uses. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has a simpler personal savings formula that calculates how much Americans save each year. It reports the annualized figures each quarter to show shorter-term trends.

The St. Louis Fed’s measure shows personal savings topping out at $4.85 trillion in the second quarter of 2020, when the pandemic was in full swing. In the first quarter of 2021, coinciding with the bureau’s high March 2021 reading, personal savings hit $3.99 trillion. Then the bottom fell out: The third quarter 2022 reading was just $520.6 billion. On a per-person basis, that’s:

- Q2 2020: $14,608.43

- Q1 2021: $12,018.07

- Q3 2022: $1,568.07

So between Q1 2021 and Q3 2022, personal savings dropped by $10,450 per American.

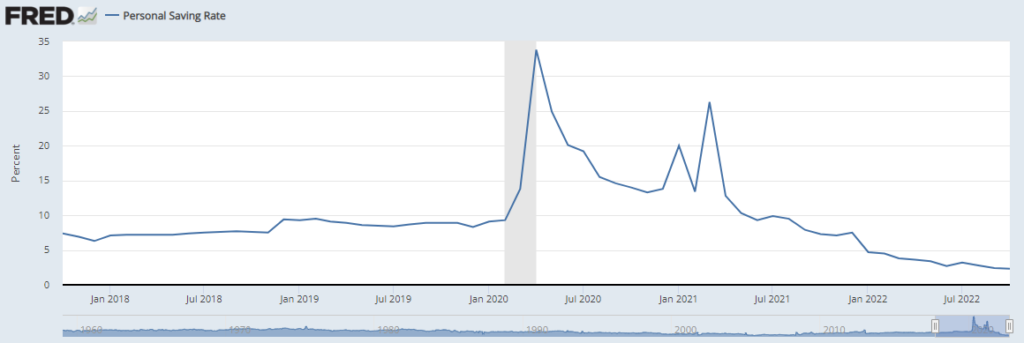

Another way to measure changes in personal savings is the personal savings rate, which measures the percentage of disposable income Americans save on a monthly basis if kept up for a full year. The trend looks familiar:

We see that the personal savings rate skyrocketed in early 2020 as the pandemic set in. It reached 33.8% in April 2020 before falling just as sharply, then bounced back up to 26.3% in March 2021 as fresh government stimulus checks arrived.

That bounce didn’t last. By June 2021, the personal savings rate was under 10%, and it closed out 2021 at 7.5%. The October 2022 rate was 2.3%, nearly matching the all-time low of 2.1%. If current trends hold, the U.S. personal savings rate could make a new low in early 2023.

What Could We Do With All That Money?

Even going by the more conservative St. Louis Fed figure, Americans’ collective personal savings declined by more than $3.4 trillion between March 2021 and October 2022 — $3.47 trillion, to be exact.

That’s a lot of money. It’s enough to pay off Americans’ total student debt burden ($1.75 trillion) and have $1.72 trillion left over, very nearly enough to do it again.

We don’t need to pay off Americans’ student debt twice, of course. But we could pay it off once and still:

On second thought, why would we do any of that? Paying off debt is boring. Balancing budgets, even more so.

Let’s instead buy every American — old folks and newborns alike — a McDonald’s Big Mac meal at $5.99 a pop. Then let’s buy them each 863 more.

Maybe Burger King can get in on the action if they ask nicely. We’ll see.

Why Did Personal Savings Spike in 2020 and 2021?

Back to reality.

The personal savings rate jumped almost overnight in the first quarter of 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold and large swathes of the global economy shut down. These are the three primary factors that drove the eye-watering increase.

Widespread Fears of an Economic Depression

Facing an unprecedented public health emergency of unclear duration, policymakers around the world had reason to fear that the COVID-19 pandemic would gravely damage the global economy and set up a rerun of the Great Depression (or worse). So did regular folks wondering what the pandemic would mean for their personal finances.

For most people, even those who kept their jobs through those dark early days, the natural response was to dramatically reduce discretionary spending. Coupled with massive job losses in industries dependent on in-person activity — the unemployment rate spiked above 14% in April 2020 — consumer spending cratered. Much of that money ended up in savings accounts, at least temporarily.

Widespread Business Closures in Key Industries

Most travel and hospitality businesses went on hiatus or severely curtailed operations when the pandemic hit. Retail was also hard-hit.

People still ordered takeout and bought stuff online, but they weren’t getting on planes or staying in hotels or eating fancy meals in restaurants. Even if they weren’t inclined to cut back spending amid all the uncertainty, their budgets for fun were much smaller by necessity. Many chose to save the surplus.

Multiple Rounds of Government Stimulus

The worst-case scenario predictions about the global economy didn’t come to pass — in large part due to massive, coordinated stimulus by governments around the world.

Here in the United States, the first of three stimulus checks arrived in April 2020, showering most taxpayers with $1,200 in tax-free cash. People who weren’t living paycheck to paycheck could afford to sock this payment away, and many did. A $600 check followed in late 2020, followed by a $1,400 payment in early 2021. That last payment coincided with a big jump in personal savings in March 2021, to $17,269.61 per person in the more comprehensive Bureau of Economic Analysis measure.

Businesses got in on the action too thanks to the Paycheck Protection Program, which unloaded hundreds of billions of dollars. These payments helped business owners keep the lights on (and pay employees) during the pandemic, but recipients weren’t required to spend all the cash on payroll or rent, so much of it ended up in the bank.

Why Did Personal Savings Collapse in 2022?

The personal savings rate dropped significantly later in 2020 but remained elevated by historical standards. It jumped again in the first quarter of 2021, then began a long decline that accelerated in 2022.

Several factors were responsible for the drop.

No More Pandemic Stimulus

The last stimulus payment went out the door in March 2021. The last PPP round closed two months later. Extended unemployment benefits, eviction moratoria, state and local aid — all but the student loan payment pause have long since ended.

That means there’s less money sloshing around the system. People have to rely on the income sources that sustained them before the pandemic, such as wages, business income, retirement income, and government benefits.

Higher Prices & Falling Real Incomes

Money doesn’t go as far with inflation at 40-year highs. Prices rose 8% compared to the same period last year for much of 2022, four times faster than the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target. Wages rose at a brisk pace too, but not quickly enough to keep up — meaning real incomes fell after accounting for price hikes.

That’s putting the squeeze on lower- and middle-class consumers and some higher earners too. They’re forced to dip into their savings to make ends meet or at the very least spend more of what they earn on necessities like housing, food, and utilities.

Slower Economic Growth

Savings rates often increase during periods of slower economic growth. We saw this during the Great Recession and for years after, when households slowly unwound the debt they’d accumulated during the housing boom and put away money for the next rainy day.

The current slowdown isn’t typical, though. It’s more like the persistent stagflation of the 1970s, a decade marred by high inflation and underwhelming economic growth. Until inflation returns to something approaching normal, today’s slower-growth environment finds households spending more of what they earn or even dipping into their existing savings to make ends meet.

Households can only spend more than they earn for so long. Eventually, their savings deplete and they’re faced with a choice: cut spending or go into debt.

Either scenario is bad for the economy. Slowing consumer demand helped tip the U.S. into the early-2000s recession, and excessive household debt foretold the Great Recession. Because the Federal Reserve seems set on raising interest rates until consumer spending buckles, my money is on a demand-induced recession in 2023 rather than a debt-induced one.

If and when that happens, we’ll see households bank more of the cash they would have spent on things and experiences. The savings rate will stop falling and then begin to increase. Absent some unknowable future shock of a similar scale, it won’t again reach the heights of the early COVID-19 pandemic, but I’d bet on a slow, steady return to the 5% to 7% range by 2026.

Since January 2022, Interest Rates Have Skyrocketed

One reason I’m confident 2022’s super-low savings rate isn’t a new normal is that consumer interest rates are higher than they’ve been in many years. Certificate of deposit rates haven’t been this high in 15 years, and high-yield savings accounts are finally living up to their promise. If you have cash to save, it’s a fantastic time to do so.

We have the Federal Reserve to thank for this saver-friendly turn of events. The Fed has relentlessly hiked the federal funds rate since early 2022, raising this key benchmark from near zero to 4.25%. That’s the fastest pace since the early 1980s and the biggest percentage jump in history.

The Fed’s stated goal is to get inflation under control by reducing demand for goods and services, but its campaign has the side effect of forcing banks to pay more for consumer deposits. And with personal savings at near-historic lows, banks have to compete fiercely for the relatively few dollars available, adding to the upward pressure on prevailing savings rates.

Now Is the Time to Save

If you have spare cash — or can raise it by trimming spending or boosting your income — now is an excellent time to increase your personal savings rate.

Interest Rates Are Already Higher Than They’ve Been in Years

The federal funds rate now tops 4%, higher than it has been since the Great Recession. That’s pushing up bank account yields. The most generous high-yield savings accounts now pay 4% interest or better, and longer-term CDs have even higher yields.

These yields don’t yet beat inflation, but they’re getting close. And with the rate of price increases expected to fall in 2023, they’ll likely get more attractive over time even if interest rates don’t rise further.

Interest Rates Will Go Higher & Remain Elevated Through 2023

Interest rates will probably rise further. The Federal Reserve is expected to hike the federal funds rate by at least 0.25% in early February 2023. Fed watchers expect another 0.25% hike in March 2023.

After that, all bets are off. The most likely outcome is a several-month pause during which the Fed leaves interest rates where they are, which at that point would be between 4.75% and 5%. They’ll use this period to gather more data on inflation, employment, and other measures of economic health. If and when it looks like we’re headed for (or already in) a recession, the Fed may begin lowering interest rates.

But that probably won’t happen until the second half of 2023, if not later. Until then, banks will raise deposit account yields in response to the Fed’s expected increases, then hold them steady until the Fed acts again. By May or June 2023, the best high-yield savings accounts could yield 4.5% or better, and the most generous 12-month CDs could pay 5%.

So you still have time to build and benefit from a big savings cushion. Savings yields aren’t heading back toward 0% anytime soon.

The Stock Market Could Underwhelm in the Coming Years

Historically, the broad-market S&P 500 stock index — which contains the 500 largest public U.S. companies and is a good proxy for the stock market as a whole — returns 8% to 10% per year, depending on where you start and how you calculate returns. But that’s a multidecade average that includes plenty of long bear markets, or periods of flat or declining returns.

It has been a while since we’ve seen a proper bear market. The S&P 500 bottomed out at 676 on March 9, 2009, then went on a mostly uninterrupted tear for the next 12 years. In January 2022, it touched an all-time high around 4,800, more than seven times its Great Recession low. Other major indices followed suit.

The S&P 500 lost more than 20% of its value in 2022 and now trades below 4,000. That’s still well above its prepandemic levels, and while most investors don’t expect a full retreat, even fewer expect a new all-time high anytime soon. As in, anytime in the next few years.

In other words, the stock market probably won’t do as well in the coming 10 years as it did in the previous 10.

This doesn’t mean the world will end — although it could — or that the stock market will actually underperform savings accounts over the next decade. (It will probably outperform savings accounts, albeit with greater volatility.) But it does mean that you’d be wise to hedge your bets and keep more of what’s yours in FDIC-insured savings accounts and CDs, especially if you’re risk-averse by nature or nearing retirement.

Final Word

Americans collectively built up an historic personal savings reserve during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two years later, most of it was gone.

That’s sobering to think about, even scary. The rapid savings drawdown occurred amid sky-high inflation, falling real incomes, and an increasingly uncertain global economic outlook. Despite tentative signs that inflation has peaked and real incomes are stabilizing, the economic outlook remains bleak, and there’s no guarantee things won’t get worse before they get better.

Then again, there’s a glass-half-full case to be made here. The pandemic was (hopefully) a once-in-a-lifetime shock that led to unprecedented stimulus and an unprecedented pullback in spending, which prompted people to save at unprecedented rates. When the stimulus dried up and the economy opened back up, people and businesses spent at higher rates than before, laying the groundwork for price increases that would force folks to spend down their savings — leading us here. A brief recession might ensue, but then spending and saving rates should normalize, and we’ll resume our prepandemic trajectory.

Will that rosy scenario pan out? It’s too early to tell. What’s clear right now is that it’s a very good time to be a saver. Pretty much everything else is still up in the air.